The Westman Islands, off Iceland’s south coast, is a story of survival and triumph. Settled by the Norse in 875 AD, they weathered the Turkish Raid of 1627 where most of the population was taken into slavery and the 1973 Heimaey eruption that changed the landscape. Through it all the islanders have persevered, becoming a fishing hub in the 19th and 20th centuries and now a leader in marine conservation with the world’s first open-water beluga whale sanctuary established in 2019. Today the islands combine history with nature, attracting tourists and researchers and showing off a mix of history, nature and innovation. Heimaey, the main island, is the hub for the inhabitants and visitors and has new lava fields, the volcano Eldfell and the famous Killer Whale Keiko.

The Westman Islands were settled around 875 AD when Norsemen came to these remote areas in search of new lands and resources. Named “Vestmannaeyjar” after Irish slaves who had escaped their Norse captors, the islands had plenty to offer. According to the Icelandic sagas these Irish slaves killed their master Hjörleifur Hróðmarsson and Ingólfur Arnarson, Iceland’s first settler, established Norse control over the islands.

The early settlers found the Westman Islands rich in resources despite their isolation. Fishing, bird hunting and gathering seabird eggs was the main economic activity. The surrounding waters were full of fish, a stable food source and trade commodity. Seasonal bird hunting and egg gathering supplemented the settlers diet and provided feathers and down for insulation. Limited farming supplied vegetables and livestock and made the community self-sufficient.

Life in the Westman Islands was hard. The settlers built turf houses to keep out the cold and wind. Family units and communal living was key to survival in such a remote area. The island's inhabitants developed the traditional practice of using ropes to collect eggs from the cliffs, a skill passed down through generations. This was essential for survival when farming conditions were not favorable and even today egg collection on the smaller off-islands is part of the local tradition. The isolation allowed the settlers to develop their own culture and traditions, different from the rest of Iceland. By the 10th and 11th centuries the Westman Islands had become a small self-sufficient community with connections to mainland Iceland, trading for grain, metal tools and other necessities.

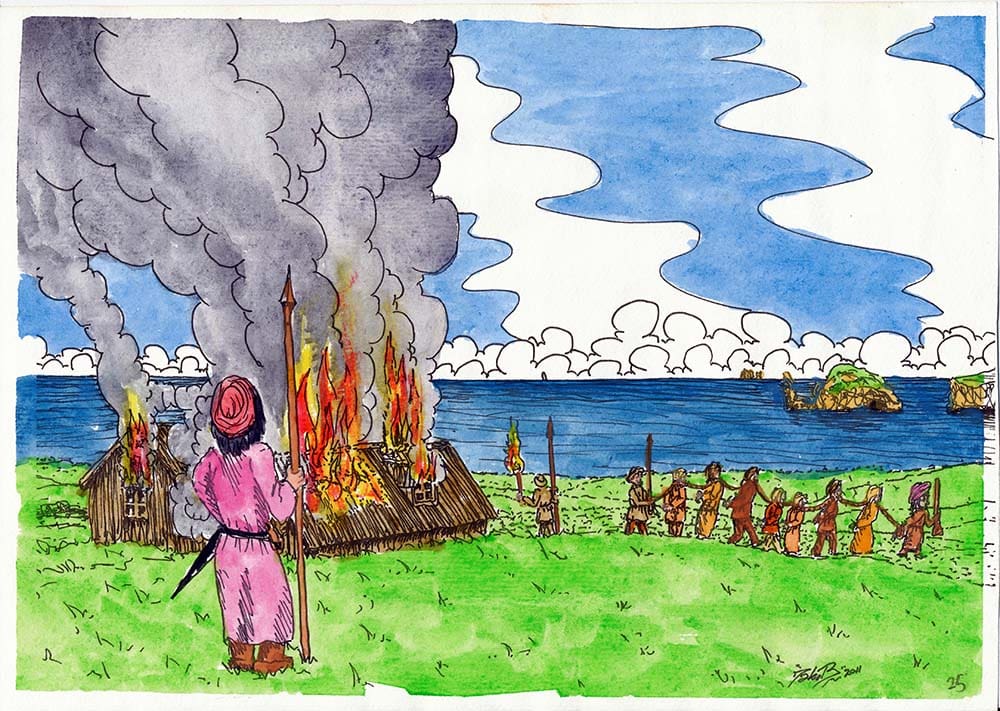

In 1627 one of the worst days in the history of the Westman Islands happened. Pirates from North Africa, often called Turkish or Algerian pirates, raided the islands and took about 240 inhabitants into slavery and devastated the community. Led by Murat Reis the pirates targeted the Westman Islands for their isolation and the vulnerability of the inhabitants.

The raid started on July 16th 1627 and the pirates quickly overpowered the islanders, capturing men, women and children. The captured inhabitants were taken across the Atlantic and sold into slavery in North Africa, mostly in Algeria and Morocco. This left the Westman Islands in shock, many families were torn apart and the community was deeply scarred. The raid led to increased fortification and vigilance as the remaining inhabitants sought to protect themselves from future attacks.

Efforts were made to ransom the captured islanders and some were eventually returned to Iceland but many remained in slavery for the rest of their lives. The raid became a symbol of the islanders ability to survive external threats. Annual commemorations and historical accounts have kept the event alive in the Westman Islands’ memory. Today the Turkish Raid is seen as a key part of the islands’ history, proof of the community that survived and continued to exist despite such great hardship.

The 19th century was a time of big change in the Westman Islands, especially on Heimaey the only inhabited island. As Iceland went through the Industrial Revolution and global trade increased the islands saw big changes in their economy, infrastructure and society. This was the era of the expansion of the fishing industry which became the backbone of the islands’ development. Heimaey Island is also known for its murals, street signs and its historical and geological significance related to volcanic activity. The Westman Islands Heimaey Island is a treat for visitors with its many works of art and street decorations.

Traditional fishing methods gave way to modern techniques and equipment and bigger catches and more efficiency. The introduction of decked fishing boats and later motorized vessels changed the industry, allowing fishermen to go further out to sea and access richer fishing grounds. This growth boosted the local economy, created jobs and stimulated growth. The population of the Westman Islands increased and infrastructure was developed to support the growing community.

New homes, schools, churches and hospitals were built and life on the islands improved. Education became more accessible and with formal schools children received a better education and were better prepared for the future, on and off the islands. Communication and transportation links to mainland Iceland increased and the Westman Islands were more connected. Vestmannaeyjar became the main settlement and economic centre with a busy fishing port and more and more businesses and services.

The early 20th century was a time of big change for the Westman Islands, mainly driven by the fishing industry. The introduction of motorized boats and better fishing gear changed the industry, bigger catches and more growth. This was the era when the Westman Islands became one of Iceland’s main fishing centres and the community and way of life was shaped.

The introduction of motorized boats allowed fishermen to access fishing grounds that were previously unreachable, the catch increased significantly. The use of trawlers and other modern fishing methods boosted productivity even more. These technological advancements attracted investments and labour and people came to the islands looking for work and opportunities. The fishing industry became the backbone of the local economy, providing jobs not only for fishermen but also for those involved in processing, transportation and related services. Puffin hunting is also depicted in the island's artwork, including a famous mural of an islander catching a puffin.

Vestmannaeyjar the main settlement on the islands grew fast with the economic growth. New businesses, housing and infrastructure was built to support the growing population and economic activity. The harbour was expanded and modernized to handle the bigger motorized fishing boats and the increased catch. This change turned Vestmannaeyjar into a busy and lively community with a strong maritime culture. The fishing industry brought better living standards, more goods, education and healthcare.

November 14th 1963 Surtsey Island was born, a new volcanic island that rose out of the North Atlantic Ocean, 32 km southwest of Heimaey, during a volcanic eruption that lasted until June 1967. This was a unique opportunity for scientists to study the formation of a new island and ecological succession.

The eruption started underwater, as a fissure in the sea floor spewed out lava and ash. The first stages of the eruption were explosive, as hot lava met cold seawater and produced violent steam explosions. As the eruption continued, the lava cooled and solidified, and a new landmass emerged above sea level. The island was named Surtsey after Surtr, the fire giant from Norse mythology, because of its fiery birth.

Scientists from all over the world saw Surtsey as a natural laboratory to study geological and biological processes. The Icelandic government declared the island a nature reserve and made it off limits to humans to preserve its pristine state. Researchers have been monitoring the island since the beginning and documenting the changes in the landscape and the colonisation of the island by plants and animals. Surtsey’s research is still giving us valuable information about island biogeography, ecological succession and volcanic activity.

January 23rd 1973 Heimaey’s residents woke up to one of the biggest volcanic eruptions in Icelandic history. A fissure had opened on the eastern side of the island and lava and ash was flowing out. The eruption lasted until June and changed the landscape, infrastructure and the community of Heimaey. The Heimaey eruption is one of Iceland’s biggest natural disasters and shows the power of nature and the resilience of the islanders.

The eruption started just after midnight and caught Heimaey’s residents by surprise. As the lava flowed towards the town of Vestmannaeyjar, the biggest settlement on the island, the community quickly mobilised to evacuate. A severe storm the night before had brought almost the entire fishing fleet into the harbour, so evacuation was fast and efficient. Within hours almost all of Heimaey’s 5,300 residents were transported to the mainland, leaving behind their homes and belongings.

The first stages of the eruption were explosive with fountains of lava and ash clouds covering the island. The fissure eventually consolidated into a single volcanic vent and lava continued to flow. The lava was flowing towards the town and the harbour, the lifeblood of the island’s fishing industry. The Icelandic government and international experts quickly came up with a plan to save the harbour. They used big pumps and hoses to spray seawater onto the advancing lava flows and cool and solidify the lava to slow it down. This was called the “Battle for the Harbour” and was mostly successful in saving the harbour from destruction.

Despite all this the eruption was devastating. One third of the town of Vestmannaeyjar was buried under lava and ash and many homes, businesses and public buildings were destroyed. The new lava field, now called Eldfell (“Fire Mountain”) rose above the town and changed the landscape of the island. The eruption also created new land, extended the coastline of the island and increased its size. After the eruption the community had to rebuild. The Icelandic government provided a lot of support, financial aid, construction materials and expert advice. Many of the residents who had been evacuated to the mainland returned to Heimaey to rebuild their homes and their lives.

In 2006 plans were made for the world’s first open-water beluga whale sanctuary in Klettsvík Bay, Heimaey. The project was led by the SEA LIFE Trust and Whale and Dolphin Conservation (WDC) and shows the commitment of the Westman Islands to marine conservation. Heimaey is the home island and the only inhabited island in the Westman Islands archipelago.

The idea for the sanctuary came from growing concerns about the welfare of marine mammals in captivity. Beluga whales are intelligent and social animals and often suffer in the confined spaces and lack of stimulation in traditional marine parks and aquariums. The sanctuary project would address these issues by providing a large open-water environment where belugas could live more freely, explore and behave naturally.

Klettsvík Bay was chosen as the site for the sanctuary because of its good conditions; sheltered waters, plenty of space and relatively low human disturbance. The bay’s natural features would provide an ideal environment for the belugas; a diverse and dynamic habitat where they could explore and be enriched. A lot of planning and fundraising went into the project and involved scientists, marine biologists, engineers and conservationists. The project faced many logistical and technical challenges; netting and barriers had to be installed to ensure the whales’ safety and prevent escapes.

The opening of the Eldheimar Museum in 2008 was a big milestone in preserving and sharing the history of the Westman Islands, especially the 1973 Heimaey eruption. Located in Vestmannaeyjar the museum is dedicated to documenting and interpreting the volcanic eruption and its impact on the community. Eldheimar is both an educational centre and a memorial, where visitors can get a unique and immersive experience of the past.

The idea for the museum came from the desire to honour the resilience and determination of the islanders who survived and rebuilt after the eruption. The exhibits are designed to show the scale and intensity of the volcanic event and the human stories of survival, evacuation and rebuilding. Through multimedia displays, interactive exhibits and preserved artefacts Eldheimar tells the story of the eruption and its aftermath.

One of the museum’s most popular exhibits is a house that was buried under lava and ash during the eruption. This house, known as the “Pompeii of the North” was excavated and restored to show the extent of the damage and how it affected the daily life of the residents. You can walk through the house and see for yourself the destruction caused by the volcanic activity and get a sense of what the community went through.

Keiko the orca who starred in the movie “Free Willy” has a special connection to the Westman Islands that shows the region’s commitment to marine conservation. Keiko’s story from his life in captivity to his rehabilitation and release into the wild was an international sensation and raised awareness about the issues surrounding captive marine mammals. His legacy continues to inspire marine conservation and shows how important it is to give these intelligent and social animals natural habitats.

Keiko was caught off the coast of Iceland in 1979 and spent years in various marine parks and aquariums where he was trained to perform for the audience. His story became well known after the release of “Free Willy” in 1993 which told the fictional story of an orca’s escape from captivity and return to the wild. The movie sparked a public outcry for Keiko’s release and a big fundraising and advocacy campaign was launched to free him.

In 1998 Keiko was moved from the Oregon Coast Aquarium to a specially built rehabilitation facility in Klettsvík Bay, Heimaey. The Westman Islands were chosen because of its good conditions; cold, clean water and relatively quiet environment which was essential for Keiko’s health and to adapt to a more natural habitat. The facility had a big sea pen where Keiko could swim freely and gradually get used to life in the wild. Despite progress Keiko still sought human interaction showing the challenges of reintegrating captive animals into the wild.

In June 2019 the world’s first open-water beluga whale sanctuary opened in Klettsvík Bay, Heimaey. The project was led by the SEA LIFE Trust and Whale and Dolphin Conservation (WDC) to give beluga whales retired from entertainment and research facilities a more natural and stimulating environment. The sanctuary is a big step in marine conservation and sets a new standard for the care and rehabilitation of captive marine mammals.

The sanctuary was born out of the growing awareness of the problems beluga whales face in captivity. These intelligent and social animals suffer in the small spaces and lack of enrichment in traditional marine parks and aquariums. The sanctuary aimed to address these issues by giving belugas a big open-water environment where they could swim, be themselves and experience the ocean’s conditions.

Klettsvík Bay was chosen because of its good conditions; sheltered waters, plenty of space and diverse marine life. The bay’s natural features was perfect for the belugas to thrive physically and mentally. The bay was modified to accommodate the whales; netting and barriers was installed to ensure their safety and prevent escapes. The sanctuary had facilities for veterinary care, feeding and enrichment activities so the belugas would get all the support they needed. The first residents Little White and Little Grey settled in well so the project was a success.

By 2021 the Westman Islands had become a tourist and marine research destination attracting visitors from all over the world with its natural beauty, rich culture and cutting edge conservation. The expansion of tourism and marine research in the islands is a perfect balance between economic development and environmental stewardship and puts the islands on the global map and makes them more sustainable.

The Westman Islands has something for everyone. One of the most popular activities is puffin watching as the islands is home to one of the biggest puffin colonies in the world. Visitors can get up close to these cute birds especially on Heimaey where guided tours will give you insight into their behaviour and habitat. The puffin population peaks during breeding season so it’s a great wildlife watching experience. Boat trips are a must for visitors to explore the islands and see the natural wonders.

Hiking is another popular activity with many trails offering stunning views of the islands’ rugged landscape and volcanoes. The hike to the top of Eldfell the volcano that formed during the 1973 eruption gives you panoramic views of Heimaey and the ocean. Other trails lead to remote beaches, bird cliffs and historical sites so you can explore the islands’ natural and cultural heritage. Boat tours gives you a different perspective of the coastline, sea caves and marine life and adds to the experience. The south coast has stunning views and is bustling with tourists so it’s a great location for visitors. Guido Van Helten has also created artwork in North Iceland, adding to the cultural richness of the region.

The Westman Islands has a rich cultural heritage and it’s on display in various museums and historical sites. In addition to the Eldheimar Museum you can visit the Sagnheimar Folk Museum which has exhibits on the history, culture and daily life of the islands. The museum has artifacts, photographs and stories that shows the ingenuity of the islanders. The Westman Islands, part of South Iceland, is known for landmarks such as the rainbow stairs, the big handset and the memorial of drowned fishermen as well as historical events like the volcanic eruptions.

The National Festival (Þjóðhátíð) is the biggest event of the year and takes place every August. This multi day event has music, dancing, fireworks and various cultural activities and is a celebration of the islanders’ heritage and community. The festival has been running since 1874 so it’s one of Iceland’s oldest and most popular traditions. The rescue center for young puffins is a major tourist attraction, you can see the birds outside of the breeding season.

Tourism has brought a lot of benefits to the Westman Islands, to local businesses, jobs and community. But it also requires careful management so the influx of tourists doesn’t harm the fragile ecosystems. Sustainable tourism practices are emphasized and efforts are made to minimize the environmental impact and raise awareness among visitors.

Marine research has also expanded in the Westman Islands due to the unique opportunities the islands offer with its diverse ecosystems and geological features. Research institutions and universities collaborate on various projects, marine biology, volcanology and climate change. The beluga whale sanctuary has added to the islands’ reputation as a marine research hub.

Tourism and research has created a win-win situation where tourism revenue funds research and research informs sustainable tourism practices. Educational programs and visitor centers provides information about the islands’ natural history and conservation efforts and helps visitors to appreciate and understand the environment.

The Westman Islands is a model for sustainable development. They are preserving their natural and cultural heritage and welcoming visitors from all over the world. Smart growth and environmental management.

As more tourists and researchers arrive the Westman Islands will keep their uniqueness and work towards a sustainable future. The growth of tourism and marine research in 2021 is a sign of the islands’ progress and their status as a North Atlantic hotspot for resilience, innovation and conservation.